An Interview with Curator Robert Cozzolino on David Lynch the Artist

By Courtenay Stallings

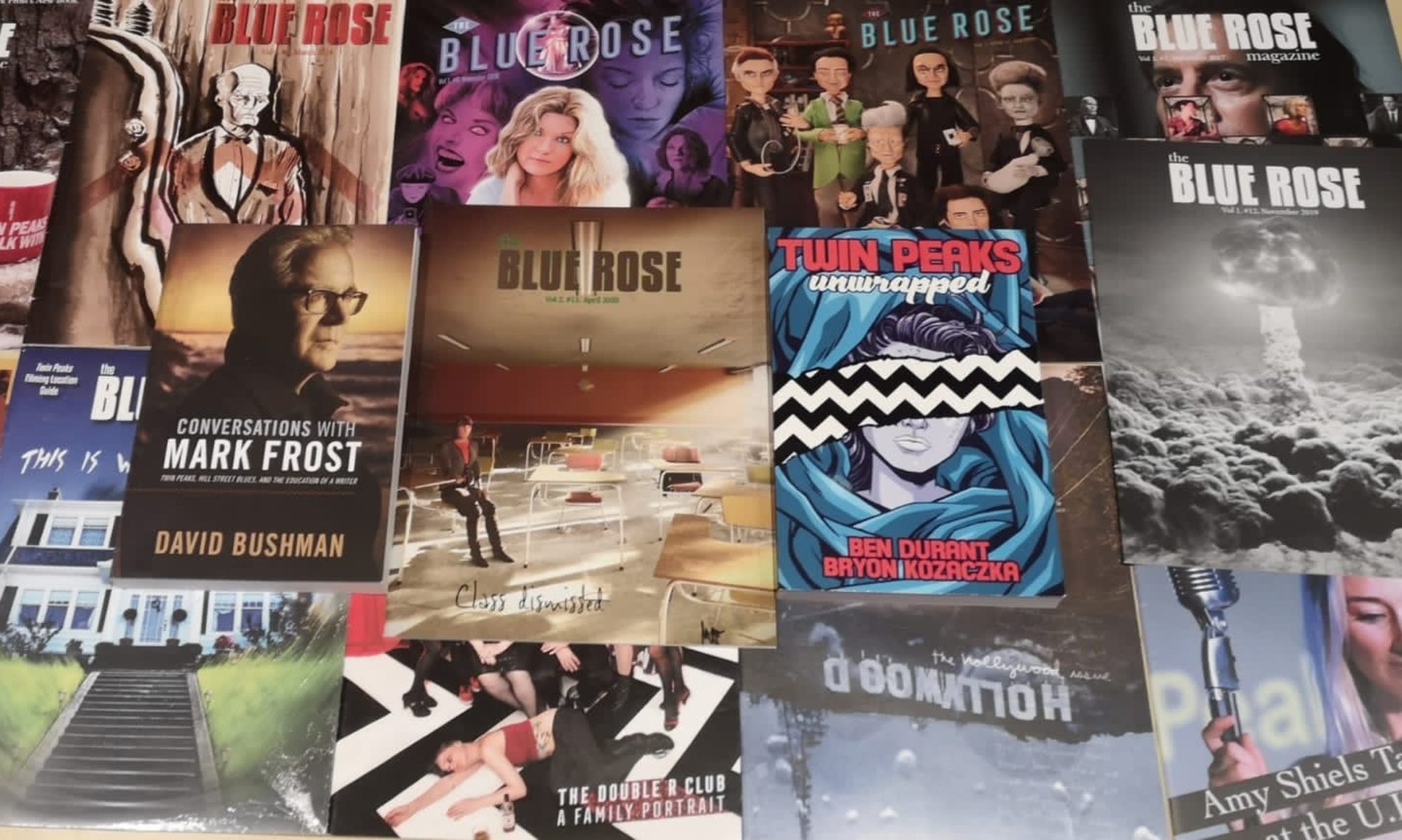

[The following is an extended version of the article that appeared in Issue 3 of The Blue Rose Magazine. Be sure to subscribe to the Blue Rose for more coverage of Twin Peaks.]

Subscribe NOW to get Issues 5-8 of The Blue Rose Magazine

At the same time David Lynch was participating in The Art Life (2016) documentary and developing Season 3 of Twin Peaks (2017) with Mark Frost, he was collaborating very closely with the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) on his first major art exhibition in the United States — David Lynch: The Unified Field — which opened in 2014 and explored his art from his early years at PAFA to his later work through 2013. The exhibition brought together 90 paintings and drawings from 1965 to his more recent work. The exhibit also displayed several of his short films from his time at PAFA where he was a student before moving to Los Angeles to study at the American Film Institute (AFI).

Robert Cozzolino, who is currently the Patrick and Aimee Butler Curator of Paintings at Minneapolis Institute of Art, was the senior curator and curator of modern art at the PAFA for David Lynch’s The Unified Field exhibition. Cozzolino worked with Lynch to curate his life’s work as a painter and mixed media artist.

Courtenay Stallings interviewed Cozzolino in the summer of 2017 for her article “‘A Unified Field’ of Dreams” in issue #3 of The Blue Rose Magazine. The following includes portions of the interview with Robert Cozzolino.

Courtenay Stallings: How did David Lynch’s exhibition at PAFA come about?

Robert Cozzolino: I think there was a sense that he must be an overbooked star and had nothing better to do than what his old art school thinks of him. So nobody really made any overtures to him … It wasn’t until a colleague and I were talking about other alumni who should have major shows, and David Lynch came up. We thought “what if?” We were surprised when they contacted us and said “We sent your letter on to him, and he said he wants to see you.”

So the fact that it was PAFA — I think that was the thing. One of the things I came to realize while working on that project is the thing that happened to him during his formative years, particularly as a student in Philadelphia and afterwards, and the time between when he was formally involved before he left for LA. That was a really critical time creatively for him — a lot happened; a lot came together. A lot of what he figured out what he wanted to do happened in those years. And it was because of really supportive mentors and peers who were all like-minded and really wanted to make art. So that supportive atmosphere really gave him the boost he needed and the confidence he needed to just do his thing. It really meant a lot to him. He told me in our first meeting in LA when we went to go visit him that if it were any other institution to ask about this, he probably would have said no, but [said yes] because it was his alma mater (even though he didn’t graduate from there) …

There’s a number of people who David kept in touch with since the Philadelphia days, which I thought spoke volumes about who he is as a person. And then when you think about it, going back to Eraserhead, he works with the same people over and over again if what they do together makes magic. But it’s the same people he knows he can rely on over and over again like Jack Nance in Twin Peaks in the first season. … I think asking about a show in Philadelphia at the Academy touched that part of him that made it make sense to him.

CS: What year did you initially start working with Lynch to plan the exhibit?

RC: I think we reached out to him in 2010. He would accept a half-hour meeting at his place. We were there for like an hour or two hours. We sat and talked with him first. I think what he was trying to figure out was what were we up to. And also knowing that whatever a curator of an art museum says about it — don’t worry we’ll organize it — that it was going to occupy his time; that he was going to have to be involved in some way. He wanted to weigh what kind of people we were personality-wise. I think it wouldn’t have worked unless he got along with us, and he just wouldn’t have been interested. And I also think that he wanted to make sure that if it were going to happen, he was going to have some kind of time investment. …

I went out there a few times looking through files, looking through drawings and paintings, and also spending a lot of time at the house. And I interviewed him for an hour and a half or so ….

I do know that he and Mark Frost were talking about revamping Twin Peaks around the time I was doing my research, but I don’t have any idea how much they were working on it in practice, but it seemed like the years leading up to me coming to talk to him he had really been training making objects. He’d had a few shows at a gallery in New York and LA, and it was favorably reviewed, and collectors who hadn’t really collected his work were starting to collect it. I had a feeling it was just the right moment. His attention was on it. He had the confidence that while he would need to devote some time and energy thinking about it or approve decisions about stuff, he got the sense that it was going to be OK without him having all of his attention on it. That was good.

He was creating a database for the first time of all of the works of his. I worked very closely with [his assistant] on this stuff. I think it was definitely the years between 2008 and 2014, when the show happened, he was really spending a lot of time making drawings and making paintings and making objects and thinking about … tapping into the aspect of his life that had always been there but had either been in the foreground or the background depending on the kinds of projects he was doing. So the main aim of that show was to take his output as an artist seriously and to not compartmentalize it but to say this is always something he’s done, and everything he’s done as an individual artist … is coming out of the same stream. It was getting people to pay attention to that. And not to think of it as the stuff he does when he doesn’t make a film but more of this is how he thinks visually …

It’s interesting to me having worked on his show and looked at his films and thought of them as moving paintings and then going to this after so much time thinking about the relationship between the static work he does and the film work he does … there are so many motifs … the idea of the box in New York is in print. It’s in the devices through which he brings his compositions in the late 1960s in those paintings in Philadelphia. Even the fact that Cole’s office is in Philadelphia — that’s funny, but there’s a meaning to that. It’s not just happenstance that that’s where the character David Lynch plays in Twin Peaks. As he said to me, he feels like Philadelphia has been like one of his muses. It’s been the major muse for the work that he’s done so I always look for references to Philadelphia in everything that he does.

CS: Sometimes there’s a way that people see an artist versus the way the artist defines or doesn’t define themselves. Years ago, I attended a talk with Jim Dine at the High Museum of art in Atlanta, Georgia. The moderator called him a “pop artist,” but he took issue with that even though that’s how people typically label his work. Is there a difference in how Lynch defines himself as an artist versus how the public views him?

I do remember a time when we were talking in the studio, and I said to him I really wanted his show to be focused on his paintings, drawings, prints and his output as a visual artist and for that to be right there prominent in the foreground. That’s the way the show would be framed. And he said, “Oh people always say that, but they always fall back on the films.” And I said, “No, I promise you that I will treat you seriously.” Because of his success with The Elephant Man and Blue Velvet, which I think preceded the show at Leo Castelli, people were going to see him as a celebrity who paints. I think he just tried not to draw any attention to it. And he just matter of factly went about doing it without really trying to hustle in the art world. That whole aspect of what is expected of an artist that you have to have — you have to really be out there doing stuff, going to parties, being connected … I think he’s happiest when he is at his house, and he doesn’t have to go out and schmooze with people, and he can just do his thing and be with his family. That’s really important to him: being able to have the mental and physical space to be able to just make stuff and think about stuff. He doesn’t live an extremely extravagant lifestyle, and he also isn’t going out of his way to become a famous artist. I don’t think he thought that as a filmmaker, either.

In terms of how he would define himself as an artist: I don’t think he would. He’s just making things that excite him about the things that excite him. It was hard to get him to talk about anything: What does this mean here? What prompted this object? Or what prompted this scenario? Or from some of the more [surreal] paintings from the 2000s — there’s a …. There’s a woman wearing a neck brace, and she’s got an electric knife and there’s a dog, and she’s like in a hotel room, and the text on the painting is “Change the fucking channel, fuckface.” I think sometimes these are just stream-of-consciousness things that occur to him. If he made any distinction between making paintings/making two-dimensional objects and making film, which he did make some kind of distinction between the two of them, … because the physical process is different, the thinking process is slightly different.

I don’t think he actually has a lot of premeditation for the recent series of paintings and drawings that he’s done. I don’t think they are completely improvised, but I don’t think he’s doing studies…. Where, as a filmmaker, I do know that he’s very careful about that. He’s careful to let you know that things are not improvised. For instance, with Inland Empire, the only correction he made in the essay I wrote was I talked about an improvisatory process for Inland Empire because the way that I had seen him talk about it or read him talking about it was that he got an idea, and he filmed it. Then he got another idea that didn’t seem like it was connected, and maybe two ideas later that he filmed to see how they were connected. To me, that seemed like it was sort of an improvisatory process, but he was careful to correct that it wasn’t. He wasn’t improvising. He knew exactly what he was doing when he was filming scenarios — even why he was filming them. He knew what would be in them. It’s just that he didn’t know that they were connected. I know that is a very careful distinction he makes. However, talking to people and reading interviews with people who have been on the set with him — if something accidental happens on the set that is visually exciting or adds another thing to it that he didn’t realize could be there, he will embrace that.

Looking at his stills while I was curating the exhibition, he was really, really specific about what is framed in the picture. That is one of the close relationships between his two-dimensional work and his still work is that he is really thinking about picture playing. He’s really thinking about how you are framing even if it’s live action and even if it’s not just a still of something … He is really carefully controlling what the viewer is able to see. I think that’s a sensibility that comes from him originally and always having been a painter and having to think about that.

CS: Yes, and in your essay in the book based on the exhibit The Unified Field you do a really good job of outlining his process as an artist, and you kind of make those ties to filmmaker, too. There’s a part that explores how many painters want to be stationary in their work, but Lynch likes to move around, and we see this in his filmmaking, too. One of the things I’ve read a lot is “let’s not try to make sense of this” and “David Lynch has no meaning,” or “he’s just making stuff up as he goes.” You just made an interesting distinction of how Lynch can be very intentional, but he’s also working from his subconscious, and he’s very open to something happening on set. Is it a discredit to him as an artist to say that he’s just making this up as he goes along, and he’s just putting random things together? What are your thoughts about this regarding his art?

One of the things is, which is a practical one, is that when he’s in his studio, he’s in control, and it is up to him. He makes all the decisions. They can be made quick. They can be erased. They can be removed. They can be scraped away. They can be burned away. And it can only take just a couple of minutes to do any of that stuff, but when you’re responsible for a crew, or if you’re doing any production, you have to have a plan, or you’re wasting everyone’s time. Even if you’re a seasoned improviser … you’ve got to come at it with a level of preparation that’s expert.

And, when you’re committing things to film, and you have actors and people that are trying to deal with their lines and where they’re supposed to be … trying to control the scene with regard to lighting and all that kind of stuff, you can’t do a whole lot of improvisation especially if it’s something like this 18-hour movie that he has made, which has to be carefully planned out. [Regarding Season 3] I have this feeling that a lot of what happens, little things that happen along the way, are going to be critical, are going to be repeated, and there will be motifs and returning motifs coming up over and over again. You’re going to see by the end how carefully composed it is. I mean, it already is. The first episode and the slowly building of mystery and the careful attention to what, again … looking at what kind of decisions have been made about what’s in Naomi Watts’ (Janey-E’s) kitchen — those kinds of things. Because I know he thought about it and had to approve it. Also, he’s so against product placement that there’s not going to be anything remotely like that in Twin Peaks.

I think the people that think there’s just crazy stuff and a series of images, and he’s making it up as he goes along is a naïve position. You can’t really do that … he’s going to have a point to it. He’s going to have a narrative arc, and it may not be a straightforward a narrative arc in the way that Mulholland Drive is not a straightforward narrative arc, but I think you can’t underestimate how powerful his experience and how natural his work as a painter is [regarding film] — sort of adding things visually, adding things in terms of sound, adding things for an 18-foot mural that are going to come back maybe later than you realize, but you’re going to have to look at it for a long time.

There is going to be eternal rhythms to it because he is composing in the sense that a painter composes, but he is also composing in the sense that a sound artist composes. All of that is at work in Twin Peaks, and he sees these very elements as a kind of palette. That’s one of the places where in all the things he does as a creative person overlap…. It’s in Six Men Getting Sick — sound is as critical as the visual, and they work together. So that siren that goes off gives the whole thing a different effect than it would if it was just completely silent or if it was some other sound.

To read Courtenay Stallings’ essay “‘A Unified Field’ of Dreams” on David Lynch the artist, order issue #3 of the Blue Rose Magazine. Subscribe to the magazine in general at www.bluerosemag.com. For more information on the David Lynch: The Unified Field exhibit, read the book, which is based on the exhibit, by Robert Cozzolino and available at Amazon.com.

_____________

Courtenay Stallings is the associate editor and a writer for The Blue Rose Magazine

Subscribe NOW to get Issues 5-8 (including Women of Lynch coming in August)